The name of this most recent addition to our Tour Options is the Canadians’ Pursuit to the Seine. It’s part of a six-day tour that connects our four-day Normandy Tour to a single day Dieppe tour. This will be the 5th day of the tour that covers the 11 day period, from the closing of the Falaise Gap (August 21, 1944) to the Liberation of Dieppe (September 1, 1944). I believe this may be one of the most under reported, intense events of WWII. If you take the time to read the following, you will be stunned by the intensity of the battles and the number of casualties, in just 11 days. To start this one-of-a-kind tour, you will be driven from Bayeux, at the conclusion of your Battle of Normandy Tour, to Dieppe, following the route of 2nd Canadian Division, in their ‘Pursuit to the Seine’.

The tour starts in Bayeux, Normandy and ends with ‘Operation Jubilee’ in Dieppe. It is your responsibility to get to Bayeux to begin the tour and to make your own arrangements for travel when the tour ends in Dieppe. However, all other travel will be included in the tour cost.

Days 1-4 – Your tour begins in Bayeux, Normandy with Days 1-4 of the itinerary set out here – Battle of Normandy

Day 5 – To start this one-of-a-kind tour, you will be driven from Bayeux, at the conclusion of your Battle of Normandy Tour, to Dieppe in their ‘Pursuit to the Seine’, which culminates with the Canadian’s liberation of Dieppe on September 1, 1944.

First, you will drive to Grand Bourgtheroulde and the Forêt de la Londe. As you approach Bourgtheroulde you will see a monument to the men of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps and the Black Watch, who were ambushed here. To explore the Forêt de la Londe, you will visit St. Ouen-de-Tilleul, a village that was the base for the Canadian operations in the Foret. There is a striking memorial here to the 13 Canadians killed nearby. The village was also a centre for a French Resistance group known as ‘le Group 133’, who provided guides for the Canadians as they fought their way through the Foret (Forest). You will stop for lunch in the charming town of Criquebeuf-sur-Seine. The town has named many streets after Canadians who were lost here. On to Rouen, the first large city to be liberated by the Canadians. Your day ends in Dieppe, which was liberated by the 2nd Canadian Division September 1, 1944.

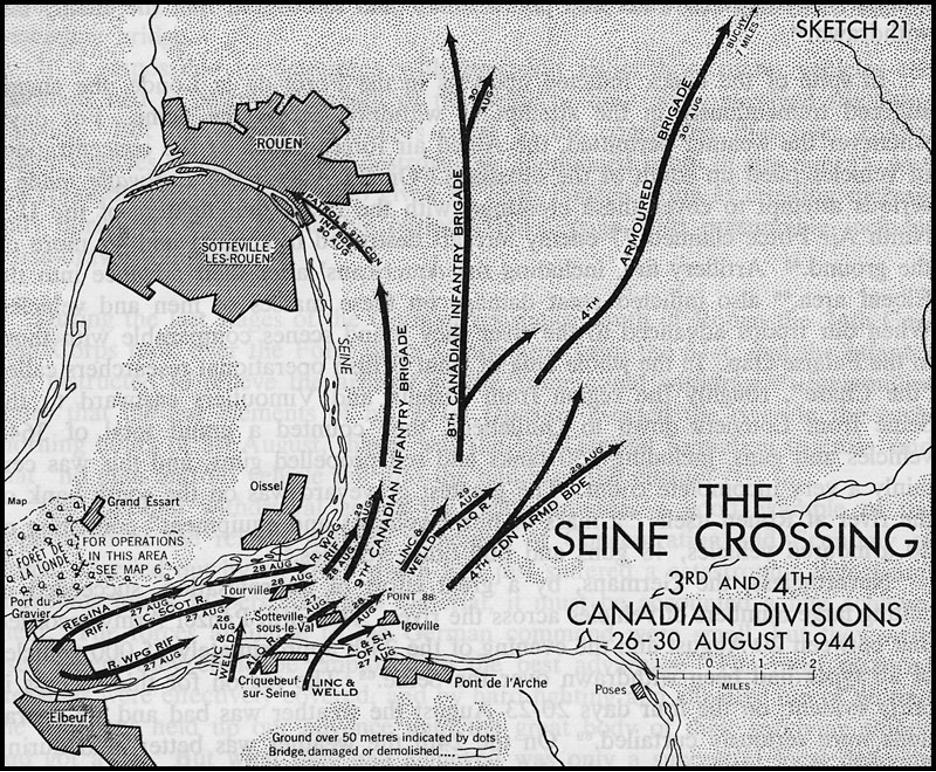

Rouen stands at the top of one of the great loops of the Seine; and across the narrow neck of this loop, ten miles south of the city, lies the Forêt de la Londe, “a rugged piece of country that would do credit to the Canadian Laurentians”. When the 2nd Canadian Division moved into the forest on the morning of 27 August they found it, contrary to report, held by a well equipped and strongly posted enemy. During the next three days the 4th and 6th Canadian Infantry Brigades sustained very heavy losses in nasty forest fighting without making much progress. Only on the afternoon of the 29th did the Germans withdraw. The next day troops of the 3rd Canadian Division, which had crossed the Seine near Elbeuf, entered Rouen. For twenty four hours thereafter, our pursuing formations poured through the sadly-scarred Norman capital, receiving a rousing welcome from its liberated people.Indeed, the most memorable feature of these days was the tumultuous and heartfelt welcome which the liberated people gave our columns. The historian of the 10th Brigade wrote later, “Will Bernay ever be forgotten? Bernay where the people stood from morning till night, at times in the pouring rain, and at times in the August sun. Bernay where they never tired of waving, of throwing flowers or fruit, of giving their best wines and spirits to some halted column.” But in every town and hamlet the reception was much the same. It was an experience to move the toughest soldier.

The enemy, improvising with great skill, had managed to pull back across the Seine, the greater part of the troops who had survived the disaster of the Battle of the Gap. Deprived of permanent bridges, he turned to pontoon bridges, which were used during the hours of darkness and folded back against the riverbank during the day; he also pressed into service great numbers of ferries. This movement, however, was harried by relentless low-flying attacks by the Allied airmen, who took a terrible toll. On 25 August the German air force, trying to cover the crossings, lost an estimated 77 aircraft in combat. “On this, and the subsequent three days”, Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory reported, “approximately 3000 vehicles were destroyed, and several thousand dead German soldiers were found among the wreckage in the area of the Seine crossings”. The destruction on the southern banks of the river was comparable to that in the Gap. Once proud enemy formations were reduced to shadows. The 2nd Panzer Division, for instance, had probably had a strength of about 15,000 men when the campaign began; now it was down to a little over 2000, with five tanks and three guns.

The Battle of Normandy was over, and the Allies had won an extraordinary victory. The German Seventh Army had for the moment almost ceased to exist as a fighting force, and the Fifth Panzer Army was in little better case. To quote General Eisenhower’s report, “By 25 August the enemy had lost, in round numbers, 400,000 killed, wounded, or captured, of which total, 200,000 were prisoners of war. One hundred and thirty-five thousand of these prisoners had been taken since the beginning of our breakthrough on 25 July. Thirteen hundred tanks, 20,000 vehicles, 500 assault guns, and 1500 field guns & heavier artillery pieces had been captured or destroyed, apart from the destruction inflicted upon the Normandy coast defences.”

General Crerar’s Army had made a very great contribution. Nowhere on the long line had the fighting been fiercer. Of the damage inflicted on the enemy, the 25,776 prisoners taken on the Army front from the opening of the offensive on the night of 7-8 August until the end of the month, represented only part; our Intelligence staff considered that the enemy’s losses in killed and wounded might be conservatively estimated at about the same figure. But we had ourselves paid heavily. Casualties of Canadian troops of the First Canadian Army for the month of August totalled 632 officers and 8736 other ranks; 164 officers and 2094 other ranks lost their lives. “The loss of these gallant officers and men”, wrote the Army Commander to the Minister of National Defence, “was the price of a most serious reverse inflicted upon the enemy”. Click on the following link for full background information on Timeline:Pursuit to the Seine:

Timeline: Pursuit to the Seine (Aug 14 – Sept 1, 1944)

August 14-15, 1944 – A new blow had fallen on the Germans, when Allied forces from Italy landed on the Mediterranean coast of France. This operation, undertaken with many doubts and after vast discussion, was a sweeping success, and as early as 11 September the men from the south joined hands with the victors of Normandy. By then almost the whole of France was free. On 25 August the world had heard the glorious news that Leclerc’s Division had entered Paris that morning. There now seemed no limit to the possibilities of the situation. After the crossing of the Seine, the question was whether the fleeing German armies could recover themselves so far as to stabilize it, even temporarily. The Battle of Normandy had made ultimate German defeat inevitable; and at the beginning of September it seemed quite probable that the final collapse could not be postponed for more than a few weeks. These hopes proved illusory. Eight months’ hard fighting still lay ahead in North-West Europe.

August 21, 1944 – Eastward Movement Begins

- With the Falaise Gap effectively closed, the 2nd Canadian Division began to shift eastward on 21 August.

- On 23 August, the remainder of the 2nd Canadian Corps, having completed their work in the Gap, joined the pursuit eastward.

August 23-24, 1944 – The advance was rapid. The Germans had sustained a tremendous reverse, and their plans were in total ruin. Nevertheless, in the words of General Crerar’s report on the operations, “In spite of the severe treatment that had been meted out to him, the enemy continued to fight stubbornly and skilfully at many points to cover the retreat of his forces across the Seine.” The British formations had bitter fighting in Lisieux and Pont-l’Évêque. The Canadians met still fiercer opposition in the Seine valley itself. On the morning of the 26th General Simonds’ leading troops reached the river, and took over from the Americans who had pushed down as far as Elbeuf. The Canadians were now close to Rouen, but the occupation of the city was delayed for several days and the Germans were able to exact a heavy price for it.

August 25, 1944 – Paris Liberated

On 25 August, Leclerc’s French Division entered Paris, a symbolic moment of liberation.This boosted Allied morale and added pressure on German forces retreating across the Seine.

August 25, 1944 – German Defensive Reorganization near Rouen

The 331st German Infantry Division was made responsible, under the 81st Corps, for covering the withdrawal across the Seine in the Rouen area. This was a good division commanded by Colonel Walter Steinmuller. It had been under the Fifteenth Army north of the Seine until early August, when it was moved south. It did not become involved in the disaster of the Pocket, but took part in the general retreat to the Seine and in it lost one of its three grenadier regiments. It now found itself defending a line west of Bourgtheroulde, while behind it a great mass of German armoured and other vehicles stood waiting to cross the river. Its task was to cover the crossings about Rouen and Duclair, at the tops of the two great loops of the Seine north and east of Bourgtheroulde. It was very evident that Steinmuller’s division would not in itself be equal to this. Accordingly, on the afternoon of the 25th Fifth Panzer Army directed Lieut.-General Graf von Schwerin, commanding the tank force that had been collected north-east of Le Neubourg, to form two armoured groups, one from the remnants of the 2nd and 9th S.S. Panzer Divisions, and the other from those of the 21st and 116th Panzer Divisions, to block the necks of the river loops south of Rouen and south of Duclair.

August 25, 1944 – General Simonds issued orders to his divisional commanders for the crossing of the Seine; They required the 4th Division to seize “by coup-de-main”(a swift attack that relies on speed and surprise to accomplish its objectives in a single blow). a bridgehead beyond the Seine in the area of Pont de l’Arche and Criquebeuf and thereafter advance directed on Forges-les-Eaux. The 3rd Division would seize in the same manner a bridgehead including Elbeuf and the railway bridge at Port du Gravier to the north. It was thereafter to advance on Neufchâtel. As for the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, it was to “clear the meander” south of Rouen and, “by coup-de-main” as in the case of the other divisions, seize bridgeheads at the railway bridge at Oissel on the east side of this loop and at the bridges at and south of Rouen. As a result of the German plans and the determination with which they were carried out, the Corps Commander’s orders proved difficult to execute.

August 26, 1944 – The 2nd Canadian Division captured Bourgtheroulde on 26 August (the Canadian Black Watch overcoming determined if disorganized opposition from snipers and a troublesome anti-tank gun in the centre of the town) and the 3rd took over Elbeuf.29 The German ferrying operations went badly this day, few units getting across the river. The Fifth Panzer Army recorded that the 86th Corps, resisting the 1st British Corps, asked for permission to remain on the south bank for another night:The Corps was therefore given orders to stand fast on 27 Aug in the line Risle Estuary-Corneville-Bourg Achard. 81 Corps was directed to fill the gap from Bourg Achard to Moulineaux with 331 Inf Div. Group Schwerin was instructed to seal off the Seine loop at Orival [just north of Elbeuf].

August 27, 1944 – the 81st Corps was standing fast on the line Bourg Achard-La Bouille-Orival. The armour was disposed with the remnants of the 9th and 10th S.S. Panzer and 21st Panzer Divisions between Bourg Achard and La Bouille, and the 116th Panzer and 2nd S.S. Panzer Divisions between La Bouille and an area north of Orival.

The 2nd Canadian Corps had reached the line of the River Risle east of Bernay, which was captured that day. Under orders issued by General Simonds on 22 August, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division was moving on the left, through Brionne, directed on Bourgtheroulde. The 3rd Division was in the centre, moving by way of Orbec upon the Elbeuf area. On the right the 4th Canadian Armoured Division was following the axis Broglie-Bernay-Le Neubourg, directed on the region about Pont de l’Arche. The advance was being led and covered by the 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons) and the divisions’ reconnaissance regiments.

The Seine, once crossed, the 2nd Corps was to establish itself in the area north of Rouen, “pushing out strong reconnaissances, preparatory to further advance in the direction of Neufchâtel and Dieppe”, We must now go back some days and deal with the 6th Infantry Brigade’s fight on the left sector of the 2nd Division front. This brigade was now commanded by Brigadier F. A. Clift, Brigadier Young having been promoted to Major General and appointed Quartermaster General in Ottawa. On 26 August the 6th Brigade was ordered to pass through the 5th Brigade, then in the Bourgtheroulde area, and clear the Forêt de la Londe. The objectives prescribed were, for The South Saskatchewan Regiment, the area La Bouille-Le Buisson; for The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, the area La Chenaie-Moulineaux, farther east; and for Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal the portion of the isthmus directly east of the railway triangle or “Y” in the northern sector of the valley through the forest.

August 27, 1944 – The infantry of the 4th Division began to cross the Seine, using stormboats, to develop the small bridgehead already held by The Lincoln and Welland Regiment opposite Criquebeuf. The 10th Infantry Brigade met heavy opposition and suffered severe casualties in attempting to enlarge this, and failed to capture the high ground north of Sottevillesous-le-Val and Igoville during the day.33 It was evident that the Germans–here, the 17th Luftwaffe Field Division34–intended to do their utmost to block any advance on Rouen from this direction. The intention of putting the 4th Division’s armoured brigade across the river in this area was abandoned, and on 28 August it crossed at Elbeuf, where there was a more secure bridgehead. The 3rd Division in fact had met little opposition in ferrying itself across the river here on the 27th; the enemy evidently had no troops to spare to try to keep us out of the low-lying river loop opposite Elbeuf, but was content to concentrate on holding the high ground, beginning some four miles east, which commanded both the approaches from Elbeuf and the 10th Brigade’s bridgehead. The 9th Field Squadron R.C.E., working under shell and mortar fire, got two tank-carrying rafts into operation at Elbeuf before nightfall, and early the next morning the 8th G.H.Q. Troops Royal Engineers completed a Bailey pontoon bridge also capable of carrying tanks.

August 26, 1944 – Canadians Reach the Seine

- Morning:

- The 2nd Canadian Division captured Bourgtheroulde, overcoming sniper and anti-tank resistance (Black Watch in action).

- The 3rd Canadian Division took over Elbeuf.

- The German ferry operations faltered under heavy Allied pressure.

- Canadian reconnaissance elements (18th Armoured Car Regiment – 12th Manitoba Dragoons) scouted ahead.

- The Seine River line was reached, but major crossings had yet to be forced.

August 26-27, 1944 – It was the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division that met the heaviest opposition in this phase, for it fell to it to attack the positions which the enemy now considered most important: those immediately covering the Rouen crossings and their approaches.

The Germans held exceptionally favourable ground. The open end of the sack-shaped loop at the top of which Rouen stands is an isthmus roughly three miles wide, covered by the eastern end of the rugged area of thick woodland known as the Forêt de la Londe. Parts of this largely uninhabited region rise as high as 120 metres above the river. A 2nd Canadian Corps intelligence summary issued on the night of 26-27 August described the enemy troops still “putting up stiff resistance” south of the Seine on our left flank as “nothing more than local rearguards”. A 2nd Division summary sent out in the afternoon of 25 August contained the statement, “Civilians report large concentration of tanks early today in Forêt de la Londe”. Incomplete records make it difficult to reconstruct the progress of planning, but at one stage the intention apparently was that the 6th Brigade should clear the Forêt de la Londe of such enemy as might be present, while the 4th and 5th crossed the Seine at Elbeuf, alternating with the brigades of the 3rd Division. But the ultimate decision was to attack the forest on the morning of 27 August with the 4th Infantry Brigade on the right and the 6th on the left. The final plan settled upon for the 4th Brigade was that it would advance through Elbeuf with The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry leading, followed by the Essex Scottish; The Royal Regiment of Canada was in reserve. The two leading battalions were to seize the high ground overlooking the river north of the hamlet of Port du Gravier, and the Royal Regiment was to pass through and take up a position just south of Grand Essart. In attempting to carry out this plan the brigade ran into the enemy’s main positions and made little progress.

Leading the brigade’s advance up the main road in the darkness, the R.H.L.I. by mistake took the left fork of the road at Port du Gravier instead of continuing on up the river. Some 500 yards north they found the road through the valley blocked. Machine-gun and mortar fire came down and the battalion was forced back to the high ground immediately west of Port du Gravier. It was clear that the enemy was strongly posted on the heights north of the valley, and the unit went on having casualties. The Essex Scottish, coming up in rear of the R.H.L.I., came under fire from Port du Gravier and took positions along the river bank.

On the morning of the 27th the brigade advanced along the road running north-east from Bourgtheroulde, except that Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal used the road running directly east. The South Saskatchewan Regiment, in the lead, soon found that the western portion of the brigade’s objectives was clear of the enemy, but the Camerons, moving east through the forest in the direction of Moulineaux, ran into strong opposition including tanks and self-propelled guns and did not succeed in taking all their objectives. As for Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, they met the enemy at Le Buquet west of Elbeuf, and pushed him back towards his main line.

Shortly after midnight of the 27th-28th Brigadier Clift issued orders for further advance. The objectives assigned were areas directly west of Oissel. However, the 6th Brigade had no better fortune than the 4th. The South Saskatchewan Regiment had got as far as the area of the railway triangle south of La Chenaie when they came under sniper and machine gun fire from the high forested ridge to the left. The leading company lost very heavily and the battalion fell back to Le Buisson and reorganized. Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, coming back under the 6th Brigade, should have followed the South Saskatchewan, but machine-gun and mortar fire kept them virtually immobilized through 28 August in the southern area west of Port du Gravier.

Another attempt was made in the evening, The South Saskatchewan Regiment again seeking to reach the high ground west of Oissel with the assistance of the Camerons, who had spent the day entrenched on their first objective west of Moulineaux and under heavy shell and mortar fire. An artillery barrage was provided, but the South Saskatchewan started late and did not get the full benefit of it. The battalion advanced east along the escarpment overlooking the Seine, past the castle of Robert the Devil on the col above Moulineaux (captured by the Germans in the 1871 battle, and called in the South Saskatchewan diary “the monastery”). It was again held up near the “Y”. The Acting C.O., Major F. B. Courtney, was killed when his carrier struck a mine. Further efforts during the night and early morning had little better result; and at first light on the 29th an enemy counter-attack pushed the South Saskatchewan back to the col. They had suffered very heavily, and continued to suffer during the day. In the afternoon a newly-arrived reinforcement officer was killed by a sniper before he could join his company. The Camerons were nearby (their C.O., Lt.-Col. A. S. Gregory, was wounded and evacuated in the course of the day). Brigadier Clift planned to use them and the South Saskatchewan in a further attack. Before this could be done, however, the brigadier himself was wounded. Lt.-Col. J. G. Gauvreau of the Fusiliers took over. On the afternoon of the 29th General Foulkes cancelled the proposed attack and ordered the brigade merely to consolidate on the line of the valley. That evening the South Saskatchewan had another misfortune; deceived by what was apparently a fictitious message originated by the enemy, they fell back some distance. Subsequently the remnants of the battalion* moved forward once more, supported by tank and artillery fire, and re-established themselves around the castle. During the night the enemy withdrew.

The brigade commander, Brigadier J. E. Ganong, ordered the reserve battalion, the Royal Regiment, to make a wide flanking movement to the north-west, cross the Port du Gravier-Moulineaux road and get behind the enemy positions holding up the other battalions. This advance, beginning about 11:30 a.m. on the 27th, made slow progress through the woods. During the afternoon the Royals made contact with Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, who were advancing on the 6th Brigade’s right; and a little later Divisional Headquarters placed the Fusiliers under command of the 4th Brigade. The Royal Regiment’s attack across the road was cancelled, and it was ordered instead to move northward to a rendezvous in the woods where the Essex Scottish was to join it.40 This junction however was never made, and the brigade commander was forced to report late that evening.

Attack arranged for this afternoon bogged down entirely in thick wood. Have ordered units concerned back to South. As soon as location received from Essex I intend to put on attack on South Objective with Essex and on North Objective with Fus MR.

Shortly before midnight General Foulkes conferred with Brigadier Ganong42 and plans were made for the next day. The Royal Regiment was to make a further attempt to out-flank the machine-gun positions dominating the line of advance, while the Essex tried again to punch through on the right. Les Fusiliers MontRoyal now reverted to the 6th Brigade.

August 28, 1944 – The 5th Brigade was moved up on 28 August to support the units fighting in the Forêt de la Londe. The Calgary Highlanders, taking over the positions west of Moulineaux formerly occupied by the Camerons, were painfully pounded with shell and small arms fire throughout the 29th, and suffered very considerably.The weather was rather poor for flying on 28 August and very poor on 29 August, deprived our troops of any effective air support.

The 4th and 6th Brigades suffered very heavily in this business. Of the battalions, only Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal (which as we have seen went into the battle already very weak) got off lightly, with 20 casualties for the three days 27-29 August. The South Saskatchewan Regiment suffered 185 casualties, 44 of them being fatal. The Royal Regiment of Canada had 118 casualties, the Camerons 99, the Essex Scottish 96, and the R.H.L.I. 59, making a total for the six battalions of 577. Lt.-Col. F. N. Cabeldu took command of the Canadian Scottish Regiment.

Early in the morning, the Royal Regiment, then in position near a flag station or “halt” in the middle of the isthmus on the more westerly of the two railway lines through the valley, began an attack intended to capture a dominant area of high ground designated “MAISIE”, whose western portion formed a salient angle in the eastern wall of the valley, through which the other railway line tunnelled. Just as the move was about to begin, rations and water arrived. The battalion diary indicates the conditions under which the troops were fighting:

As the men had, generally speaking, been without water for about 18 hours and without food, except for odd scraps which they had carried with them, for a longer period, the Acting CO [Major T. F. Whitley] took it upon himself to allow the troops to eat and fill their water-bottles before starting the move. This resulted in “C” Coy crossing the start line at first light instead of in darkness, but it is extremely doubtful whether the darkness would have assisted our troops in any way as enemy positions had not been pinpointed.

“C” Company’s immediate objective was “Chalk Pits Hill”, another but lower salient feature north-west of “MAISIE”. It failed to capture it, and suffered heavily in the attempt. Major Whitley now called for artillery concentrations to prepare the way for a battalion attack. This took time to arrange, and “permission could not be obtained to lay down a medium concentration on Chalk Pits Hill itself as the exact position of units of 6th Bde on our left was not known”. At 11:30 a.m. the battalion attacked. On the left flank Chalk Pits Hill again resisted all efforts; on the right the line of the second railway was reached and since it seemed that progress was being made the company here was reinforced with a second. However, these two companies likewise met heavy opposition and became widely separated from the rest of the battalion; and the attack again came to a stop.44

On the right of the brigade front the Essex Scottish fared no better. Two companies went forward about 1:30 p.m. after heavy preparation by artillery and medium machine-guns; but as they moved down the steep slope into the valley at Port du Gravier they met heavy fire and were forced to dig in along the road north of the village. They withdrew after night fell.45

The COs of both the RHLI and the R Regt C were strongly of the opinion that this task was beyond the powers of a Battalion composed largely of reinforcement personnel with little training. It was suggested that the enemy was actually stronger than Intelligence reports had indicated, and that the ground was immensely favourable for defence.

However, the operation was considered necessary and the R.H.L.I. made the attempt. Major H. C. Arrell was in command, since the C.O., Lt.-Col. G. M. Maclachlan (who incidentally had been wounded on 12 August but returned to duty next day) had been taken ill during or just after the orders group.47 The battalion got forward slowly, and dawn had broken on the morning of the 29th before it crossed the first railway. Heavy concentrations of artillery smoke were laid down to assist it, but machine-gun fire from the forest-clad heights stopped it. At 1:26 p.m. it reported that its three forward companies had lost heavily. Two of them had been withdrawn some distance. Heavy machine-gun and mortar fire was still coming down. The Acting C.O. felt that it was “impossible to proceed with original plan and that position must be taken from another direction”. The battalion held on for the rest of the day and then withdrew to the Royal Regiment area.

August 29, 1944 – German Withdrawal Begins

- Morning: Essex Scottish discovered German positions thinning and advanced 800 yards beyond Port du Gravier.

- Afternoon: General Foulkes ordered consolidation rather than renewed assault.

- Evening: Germans withdrew across the Seine under cover of darkness.

- Casualties (27-29 August):

- South Saskatchewans: 185 (44 fatal)

- Royal Regiment of Canada: 118

- Camerons: 99

- Essex Scottish: 96

- RHLI: 59

- Fusiliers Mont-Royal: 20

- Total: 577 casualties over three days.

August 30, 1944 – Rouen Liberated

- Morning: Canadian troops entered Rouen without significant resistance.

- For the next 24 hours, Allied columns poured through the city, were greeted by jubilant civilians.

- German remnants continued retreating across the Seine using pontoon bridges and ferries.

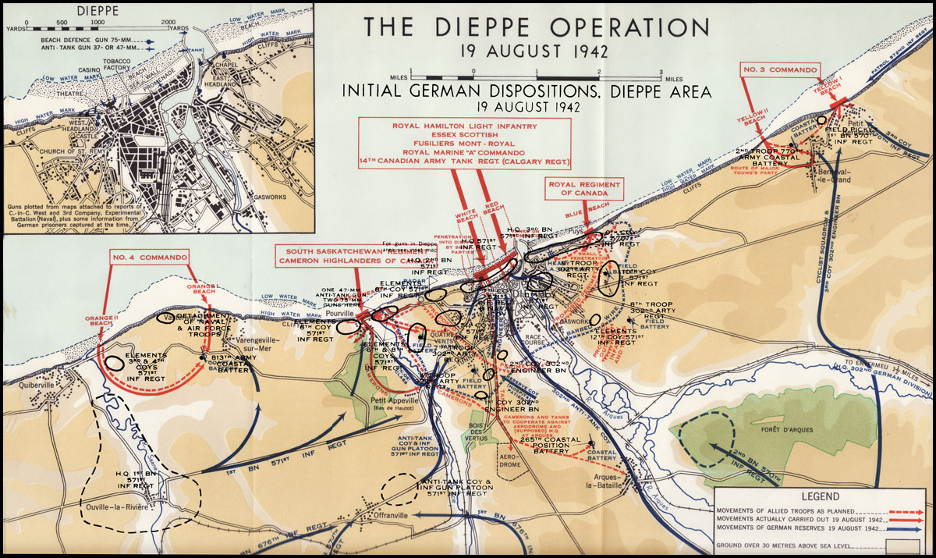

September 1, 1944 – Dieppe Liberated

- The 2nd Canadian Division reached and liberated Dieppe, the site of the tragic 1942 raid.

- The rapid pursuit brought Canadian forces to the Channel coast, completing this phase of the campaign.

Day 6 – Your day begins and ends with the events of ‘Operation Jubilee’, better known as the Dieppe Raid https://canadianbattlefieldtours.ca/dieppe-tour/

ADDITIONAL TOUR INFORMATION – As with our other tour options, this tour will be a private, personalized tour, available anytime on a first come-first served basis, ideally for groups of 1-4 people. If you have any special requests, like following the footsteps of a Veteran or unit, we are happy to accommodate, whenever possible. Just provide us the information about a soldier or unit and we will do some preliminary research, to make your tour an even more meaningful experience.

This tour, as well as our others, will be priced on the following basis. The price quoted will be for all ground transportation within the battlefield areas with professional guide(s). It does not include anything else. Of course, we are happy to make recommendations to help with your travel planning, like hotels, B&B’s. You will need accommodation in Bayeux for three nights (four nights if you arrive a day early) and Dieppe for one night (two nights if you stay after the end of the tour). There are many hotel booking sites.