History of the Devils Brigade (First Special Service Force)

WWII Italian Canadian Campaign – Devils Brigade Tour

Join us for a truly unique one-of-a-kind tour that combines and follows the path of 1st Canadian Corps and the Devils Brigade through the pivotal WWII battlefields of Italy; The horrific battles for Ortona, Anzio, Monte Cassino, Rome and much more. Please click on the itinerary link for full details. Please plan early for a tour as dates fill quickly.

Canada Remembers the Italian Campaign & The Devils Brigade

Introduction

The Second World War began in 1939. Soon, much of Europe was under German control. In 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union and vicious fighting broke out on the Eastern Front. By 1943 the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, asked for help from the other Allied leaders to ease the pressure of this attack. The Allies agreed to help and decided to use Italy (which was aligned with Germany) as a platform to attack enemy territory in Europe and help divert German resources from the Eastern Front. This effort became known as the Italian Campaign.

Canada’s longest Second World War army campaign was in Italy. Canadian forces served in the heat, snow and mud of the grinding, nearly two-year Allied battle across Sicily and up the Italian peninsula — prying the country from Germany’s grip, at a cost of more than 26,000 Canadian casualties, nearly 6,000 of which were fatal. Most of the Canadians who died in Italy are buried in the many Commonwealth war cemeteries there, or are commemorated on the Cassino Memorial, located in the Cassino War Cemetery south of Rome. More than 93,000 Canadians, along with their allies from Great Britain, France and the United States, played a vital role as they pushed from the south to the north of Italy over a 20-month period,

Canadians faced difficult battles against some of the German army’s best troops. They fought in the dust and heat of summer, the snow and cold of winter, and the rain and mud of the spring and fall.

The Conquest of Sicily

The assault on Sicily was to be the prelude to the invasion of mainland Europe. The invasion was assigned to the Seventh U.S. Army under Lieut.-General George S. Patton, and the Eighth British Army under General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery.

Canadian soldiers from the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade had an active and important role in this effort, codenamed Operation Husky.

The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, under the command of Major-General G.G. Simonds, sailed from Great Britain in late June 1943. En route, 58 Canadians were drowned when enemy submarines sank three ships of the assault convoy, and 500 vehicles and a number of guns were lost. Nevertheless, the Canadians arrived late in the night of July 9 to join the invasion armada of nearly 3,000 Allied ships and landing craft.

At the beginning of the campaign on July 10th 1943, Sicily was defended by the Italian Sixth Army with more than 200,000 men, supported by two German divisions. The landings on “Sugar” and “Roger” beaches were virtually unopposed.

Just after dawn on July 10, the assault (preceded by airborne landings) went in. Canadian troops went ashore near Pachino close to the southern tip of Sicily and formed the left flank of the five British landings that spread along more than 60 kilometres of shoreline. Three more beachheads were established by the Americans over another 60 kilometres of the Sicilian coast. In taking Sicily, the Allies aimed, as well, to trap the German and Italian armies and prevent their retreat across the Strait of Messina into Italy. The Italian defenders were quickly overwhelmed and the Canadians advanced on Pachino and its strategic airport. Nightfall saw most of the Canadian units either on or past every initial objective. Only seven men had died and 25 others were wounded. On 11 July the Canadians were delayed, not as much by enemy opposition than by thousands of Italian troops wanting to surrender. The Canadians followed an inland route that guarded the British Eight Army’s left flank up the eastern coastline toward Catania and the ultimate objective of the Strait of Messina, which divides Sicily from the Italian mainland.

With the Italian army’s rapid collapse, several German divisions hurriedly established a series of defensive lines. From the Pachino beaches, where resistance from Italian coastal troops was light, the Canadians pushed forward through choking dust, over tortuous mine-filled roads. At first all went well, but resistance stiffened as the Canadians were engaged increasingly by determined German troops who fought tough delaying actions from the vantage points of towering villages and almost impregnable hill positions. Canadian troops encountered such a line on 15 July near Grammichele, a seventeenth-century planned city built as a hexagon and perched on a long ridge. The crack of 88mm guns greeted the Three Rivers Tank Regiment and a fierce battle erupted. The Germans, of the Hermann Goering Division, retreated after the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment, the “Hasty Pees,” converged on the town with tanks and artillery support. The village was taken by the men and tanks of the 1st Infantry Brigade and Three Rivers Regiment. Enemy anti-tank guns knocked out one tank, three carriers, and several trucks before the Canadians rallied and carried the town. Having inflicted 25 Canadian casualties, the Germans withdrew.

Canada’s “Mountain Boys”

On 18 July the Canadians met their heaviest resistance to date at Valguarnera. Fighting before the town and on adjacent ridges resulted in 145 casualties, including 40 killed. But the Germans lost 250 men captured and an estimated 180 to 240 killed or wounded. Field marshal Albert Kesselring reported that his men were fighting highly-trained mountain troops. “They are called ‘Mountain Boys,’ he said, “and probably belong to the 1st Canadian Division.” German respect for the Canadian soldier was beginning.

For the next 17 days, the Canadians were hotly engaged. At Leonforte, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade spent a night of house-to-house fighting. Meanwhile, the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment carried out one of the most spectacular exploits of the campaign. Carrying little except rifles and Bren guns, they scaled the 904 metre high mountain terraces leading to Assoro, single file in partial moonlight, to surprise the German defenders,. After a forty-minute climb on goat tracks they dug in on the edge of town, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy when counterattacks were mounted. Despite the defensive advantages which mountainous terrain gave to the Germans, after bitter fighting both places fell to the Canadian assault. Piazza Armerina and Valguarnera fell on successive days. Even stiffer fighting was required as the Germans made a determined stand on the route to Agira, where the Canadians suffered their heaviest loss of the campaign (438 casualties), Agira could not be captured until the Loyal Edmonton Regiment and the Seaforth Highlanders scaled the peaks over-looking the town. Three successive attacks were beaten back before a fresh brigade, with overwhelming artillery and air support, succeeded in dislodging the enemy. On July 28, after five days of hard fighting at heavy cost, Agira was taken. Meanwhile, the Americans were clearing the western part of the island and the British were pressing up the east coast toward Catania. These operations pushed the Germans into a small area around the base of Mount Etna where Catenanuova and Regalbuto were captured by the Canadians.

The final Canadian task was to break through the main enemy position and capture Adrano. Here, they continued to face not only enemy troops, but also the physical barriers of a rugged, almost trackless country. Mortars, guns, ammunition, and other supplies had to be transported by mule trains. Undaunted, the Canadians advanced steadily against the enemy positions, fighting literally from mountain rock to mountain rock.

By the first week of August, the Germans were caught in a closing vice of American, British, and Canadian units. On 17 August, the Germans evacuated Sicily. By then, the Canadians had marched 210 kilometres and suffered 2,310 casualties, including 562 dead.

With the approaches to Adrano cleared, the way was prepared for the closing of the Sicilian campaign.

Taking Sicily was important. It helped secure the Mediterranean Sea for Allied shipping and contributed to the downfall of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. The new Italian government surrendered to the Allies; however, the Germans were not prepared to lose Italy and seized control. The fall of Sicily cleared the way for the Allies’ next step: landing in mainland Italy.

Sicily had been conquered in 38 days. The Sicilian campaign was a success. Although many enemy troops had managed to retreat across the strait into Italy, the operation had secured a necessary air base from which to support the liberation of mainland Italy. It also freed the Mediterranean sea lanes and contributed to the downfall of Mussolini, thus allowing a war-wearied Italy to sue for peace. Mussolini was deposed at the beginning of the campaign, one of the major goals set for this offensive. The landings in Sicily were also an important factor in Hitler’s decision to end the offensive operations in Russia.

Operation Husky was a strategic victory of great value. The Canadians in Sicily had lived up to their First World War reputation, fighting with skill and determination. They had fought through 240 kilometres of mountainous country—farther than any other formation in the Eighth British Army. During their final two weeks, they had borne a large share of the fighting on the Allied front. Canadian casualties throughout the fighting totaled 562 killed, 1,664 wounded and 84 prisoners of war.

Liberating Mainland Italy

After a brief rest, the Canadians were placed in the British Eighth Army’s vanguard for the invasion of mainland Italy. A long, arduous march up Italy’s boot and the assault across the strait of Messine, began when the West Nova Scotia and Carleton and York regiments of 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade landed immediately north of Reggio Calabria on 3 September. Again, opposition came mostly in the form of Italian soldiers surrendering by the hundreds. On 8 September, the Italian government itself surrendered to the Allies. In the surrender’s wake, German troops raced to intercept the Allied advance by withdrawing to establish their line of defence across the narrow, mountainous central part of the peninsula. The Canadians captured Reggio, and advanced across the Aspromonte Mountains and along the Gulf of taranto to Catanzaro. In spite of rain, poor mountain roads, and German rearguard actions, they were 75 miles inland from Reggio by September 10.

Southern Italy’s rugged country was ideally suited for defence. It took the Canadians two weeks in October to advance just 40 kilometres from Lucera to Campobasso. This stubborn fighting withdrawal by the Germans bought them time to create a fortified system of defensive lines well south of Rome. Dubbed the Gustav Line, the system hinged on the high point of Monte Cassino in the west and the Sangro River in the east. On 28 November, British troops assaulted the Sangro River. After nearly a week of heavy fighting, the Germans pulled back from this river to a new line behind the Moro River.

To slow the Allied advance, the Germans took advantage of the mountainous landscape and turned the length of the Italian peninsula into a series of defensive positions which stretched from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic Sea. These defensive lines were well protected with machine gun nests, barbed wire, land mines, and artillery positions.

The Eighth British Army (including the 1st Canadian Division, the 5th British Division and the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade) would lead the way across the Strait of Messina to the toe of Italy and then advance toward Naples. The Fifth U.S. Army (with two British and two U.S. divisions) would make a seaborne landing in the Gulf of Salerno, seize Naples and advance on Rome. The 1st British Airborne Division would land by sea in the Taranto region and seize the heel of the peninsula.

Meanwhile, the Fifth U.S. Army met stiff German resistance as it assaulted the beaches of Salerno. To assist American troops in the breakout from the bridgehead, a Canadian brigade was diverted from the main Canadian line of advance to seize Potenza, an important road centre east of Salerno. Potenza was taken on September 20. The breakout was accomplished, and on October 1, the Fifth U.S. Army entered Naples. In the meantime, the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade proceeded eastward, joined the British Airborne Division in the Taranto region, and then pushed boldly inland to the north and northwest. The 5th British Corps seized the Foggia airfield.

By the end of September, the German hold on northern and central Italy was still unshaken, but the Allies had overrun a vast and valuable tract of southern Italy. Allied armies stood on a line running across Italy from sea to sea. The next objective was Rome.

As the Allies drove north from Naples and Foggia, the Canadians found themselves pushing into the central mountain range. Now the enemy resisted with full force. On October 1 at Motta, the Canadians fought their first battle with Germans in Italy, and a series of brief, but bloody actions followed. On October 14, the Canadians took Campobasso. The next day they took Vinchiaturo and the advance continued across the Biferno River. During the same period, one unit of the Canadian Army Tank Brigade played a distinguished role on the Adriatic coast by supporting a British assault at Termoli and its advance to the Sangro River.

In the 63 days since landing, the Eighth British Army had covered 725 kilometres. The “pursuit from Reggio” was over, however, as the Germans were prepared to make a stand from the coast south of Cassino on the Naples-Rome highway, to Ortona on the Adriatic shore. The German strength was now almost equal to that of the Allies and they had the advantage of being on the defensive. The liberation of Rome would not be easy.

Meanwhile, the decision had been made to strengthen the Canadian forces in the Mediterranean. On November 5, the Headquarters of the 1st Canadian Corps under Lieut.-General H.D.G. Crerar and the 5th Canadian Armoured Division arrived in Italy. General G.G. Simonds took over command of this division and was replaced in the 1st Division by Major-General C. Vokes. General McNaughton, who had objected to the division of the Canadian Army, retired soon afterward.

As the first snow of winter began to fall, the Eighth British Army struck hard at the German line along the Sangro River on the Adriatic Coast. The aim was to break the stalemate that had developed and relieve the pressure on the Fifth U.S. Army in the drive to take Rome. The task was not easy as the Adriatic shoreline was cut by a series of deep river valleys. The British and Canadians succeeded in driving the Germans from the Sangro but were faced with the same task a few kilometres further north. Here, along the line of the Moro River, some of the most bitter fighting of the war took place. The Germans counter-attacked repeatedly and often the fighting was hand-to-hand as the Canadians edged forward to Ortona on the coast.

Further offensives ground to a halt due to atrocious winter weather. During the lull, Simonds left for England and Major-General E.L.M. Burns succeeded him. In March, Burns took over the 1st Canadian corps from Lieut.-General Crerar, who returned to command the First Canadian Army in England. The 5th Canadian Armoured Division was taken over by Major-General B.M. Hoffmeister.

By now the Canadian Army in Italy had reached its peak theatre strength of nearly 76,000. Total casualties in the Corps had climbed to 9,934 in all ranks, of which 2,119 had been fatal

Fighting in the Italian Campaign continued as the Allies made their way north through many German defensive positions. Notable for Canada was the Battle in the Liri Valley, with the ensuing liberation of Rome by the American army on June 4, 1944. In the late summer and fall of 1944, the Allies broke through Germany’s “Gothic Line” in the north. Fighting continued into the spring of 1945 when the Germans finally surrendered. By February 1945, the Canadians had been transferred to Northwest Europe to be reunited with the First Canadian Army. There they joined the Allied advance into the Netherlands and Germany to help finally end the war in Europe.

The Germans settled in for the winter on a line drawn across the narrowest, and highest, part of the Italian peninsula. The Gustav Line and Monte Cassino were turned into formidable defensive works, and the Hitler Line was prepared to defend the Liri Valley – the road to Rome.

The Sangro and Moro

The Canadians entered the battle at Moro River and on the night of December 5/6, 1943, elements of three Canadian battalions were across the river. The terrain and weather were miserable with rain turning rivers into racing torrents and the ground into thick, clinging mud. Enemy counterattacks forced a withdrawal but the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment raised in Eastern Ontario were able to re-establish a shallow bridgehead. On December 8, the Royal Canadian Regiment launched a new attack out of this bridgehead and together with the 48th Highlanders of Canada won control of the battlefield.

The end of the Gustav Line settled in the vicinity of the Sangro River, and Canadian and British attacks in the area made slow progress for high cost. Across the Sangro lay the Moro River, which took three days to cross, followed by fighting at a feature called The Gully, which saw attack and counter-attack over the period 10 to 19 December.

Battle of Ortona – December 23-28

The fighting shifted towards the small port city of Ortona. One of the most difficult battles for the Canadian troops, during the Christmas of 1943. Ortona was an ancient town of castles and stone buildings located on a ledge overlooking the Adriatic Sea. Its narrow, rubble-filled streets limited the use of tanks and artillery. This meant the Canadians had to engage in vicious street and ‘house by house’ fighting and smash their way through walls and buildings-“mouseholing”, as it was called- blasting through walls and lobbing grenades to clear the staircases and upper floors. Here the Canadians wrote the book on street-fighting.

The Canadians liberated the town on December 28 after more than a week of struggle and heavy fighting outside the town and within took place. The fight for the city became known as “Little Stalingrad” in the press. Shortly after Christmas, the city was abandoned by the Germans, and the Canadians settled in to a three month period of stalemate on the Arielli Front. During that time the headquarters of I Canadian Corps became operational, as the 5th Canadian (Armoured) Division arrived in theatre.

Ortona was a victory for all of the Canadian troops – and all Canadians. Ordinary men, volunteering to leave civilian life behind because they were needed, had forged regimental extended families and small cohesive units that fought with skill and determination. Captain Paul Triquet of the Royal 22nd Regiment was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions in Casa Berardi, a small town overlooking Ortona.

The battle was just one part of a larger Allied offensive designed to secure the main East-West highway in Central Italy and outflank the German defences south of Rome. It is one of the best known battles fought by the Canadians in the Second World War: a battle of great innovation and adaptation in which the rifle companies had begun the operation at little better than half-strength. All the hardware of the infantrymen was brought to bear against this entrenched foe. Anti-tank shells could not blast through the thick walls so they were aimed through windows where they would ricochet, inflicting horrible damages.

Cassino

As the Canadians waited out the winter on the Arielli Front in a series of patrols and small unit actions (including the first combat actions of the 5th Canadian (Armoured) Division), the fighting at Anzio had also quickly reached a stalemate. Intended to put the Allies in Rome, a timid expansion of the beachhead and a rapid German response stalled the attack for four months. The Allied command looked to Monte Cassino for a solution. Several armies had tried to take the heights at Cassino, including the Americans, the Free French, and the New Zealanders. The commander of the 15th Army Group, General Harold Alexander, opted to assault along a broad front with as many formations as possible. American, French, British and Polish formations lined up on a 35-kilometre wide line, and once they attacked, the Anzio force, too, would try once more to break out. Canadian tanks assisted in the initial attacks at Cassino beginning on 13-14 May 1944, while the Canadian Corps waited in reserve to play its part in the breakout down the Liri Valley.

The Battle in the Liri Valley

In the spring of 1944, the Germans still held the line of defence north of Ortona, as well as the mighty bastion of Monte Cassino which blocked the Liri corridor to the Italian capital. The British and Indian XIII Corps failed to break the Hitler Line as planners of the Cassino battle had hoped, and I Canadian Corps was moved up in the middle of May to take on the task. The line was heavily wired and mined and studded with concrete emplacements and armoured gun turrets. Nonetheless, at the cost of 1,000 casualties, the Canadians breached the line in a day, inflicting almost as many casualties. Other offensive actions were equally successful; the Americans crossed the Garigliano and advanced along the coast; the French Expeditionary Corps also broke through German defences, and the forces at Anzio managed to breakout as the Poles were finalizing their capture of Monte Cassino. After the Hitler Line came the Melfa Crossing, garnering a Victoria Cross for Major John K. Mahoney of The Westminster Regiment (Motor). Determined to maintain their hold on Rome, the Germans constructed two formidable lines of fortifications, the Gustav Line, and 14.5 kilometres behind it, the Adolf Hitler Line. Despite this, on 4 June 1944, Rome fell to the Allies. The battle marked the first divisional level operations of the war for the 5th Canadian (Armoured) Division.

During April and May of 1944, the Eighth British Army, including the 1st Canadian Corps, was secretly moved across Italy to join the Fifth U.S. Army in the struggle for Rome. Here under the dominating peak of Cassino, the Allied armies hurled themselves against the enemy position. Tanks of the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade (formerly 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade) supported the Allied attack. After four days of hard fighting, the German defences were broken from Cassino to the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Germans moved back their second line of defence. On May 18, Polish troops took the Cassino position and the battered monastery at the summit.

On May 16, the 1st Canadian Corps received orders to advance on the Hitler Line ten kilometres farther up the valley. Early on May 23, the attack on the Hitler Line went in. Under heavy enemy mortar and machine-gun fire, the Canadians breached the defences and the tanks of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division poured through toward the next obstacle, the Melfa River. Desperate fighting took place in the forming of a bridgehead across the Melfa. Once the Canadians were over the river, however, the major fighting for the Liri valley was over.

The operation developed into a pursuit as the Germans moved back quickly to avoid being trapped in the valley by the American thrust farther west. The 5th Armoured Division carried the Canadian pursuit to Ceprano where the 1st Canadian Infantry Division took over the task. On May 31, the Canadians occupied Frosinone and their campaign in this area came to an end as they went into reserve. Rome fell to the Americans on June 4. Less than 48 hours later, the long-awaited D-Day invasion of Northwest Europe began on the Normandy beaches. It remained essential, therefore, for the Allied forces in Italy to continue to pin down German troops.

The Canadians were now withdrawn for well-earned rest and re-organization, except for the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade which accompanied the British in the Allied action as the Germans moved northward to their final line of defence.

Advance to Florence

I Canadian Corps was taken out of the line to rest and reorganize, made changes in command, and, absorbing lessons from the costly battles of the spring, created a new infantry brigade in the 5th Armoured Division to change the balance of tanks and infantry. This new organization remained in effect until Canadian troops left the theatre in early 1945, and the brigade was disbanded before the 5th Division went into action again in North-West Europe. In the meantime, the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade continued its service to British formations during the Advance to Florence, seeing action at the Trasimene Line, Sanfatucchio, Arezzo, and Cerrone.

Gothic Line

The Canadian Corps returned to the line in August 1944 as the 8th Army was driving north of Florence to a new series of positions called the Gothic Line. (The First Special Service Force left the theatre to take part in the invasion of Southern France.) General Alexander proposed a joint attack by his two Armies on the Florence-Bologna axis, where the mountains were less rugged. His army commanders, General Oliver Leese of the 8th Army and General Mark Clark of the 5th Army, “want(ed) as little as possible to do with each other and (Leese) being particularly vehement in his opposition to a combined assault. As usual, Alexander was unwilling to assert himself; and he agreed that the Eighth Army’s attack should be shifted to the Adriatic coast while the Fifth would make the thrust towards Bologna unassisted, starting a few days later.”

For the Canadians, the main German defensive line was 7 to 8 miles from their Start Line beyond a range of hills. The attack began on 25-26 August with a largely ineffective barrage, and an opening attack by the 1st Canadian Division so slow that the 5th (Armoured) Division, in reserve, was brought up within 48 hours. Both divisions plunged into the wire, minefields, concrete and steel fortifications. The Cape Breton Highlanders attacked Montecchio three times before The Perth Regiment captured the place with a flanking move. Point 204 fell on 31 August, a key position in the German line, once again the Perths were responsible for its capture, supported by The British Columbia Dragoons. The two divisions began to leapfrog past each other. On the left, the British struggled to keep up, and left high ground in enemy hands to their rear in their haste to do so.

On 5 September, resistance from the town of Coriano stopped the Canadians. Five days of failed assaults by the British, despite offers by the Canadian corps commander (Lieutenant General E.L.M. Burns) to take the place from the flank, followed. Finally the British and Canadians attacked together on 12-13 September 1944 and inflicted 1,200 casualties. The Canadians had lost 200 men killed and wounded.

The Road to Rimini

Autumn and winter 1944 saw the Canadians back on the Adriatic coast with the objective of breaking through the Gothic Line. This line, running roughly between Pisa and Pesaro, was the last major German defence line separating the Allies from the Po Valley and the great Lombardy Plain in northern Italy. Since many factories producing vital supplies were located in the north, the Germans would fight hard to prevent a breakthrough. The line was formidable, composed of machine-gun posts, anti-tank guns, mortar- and assault-gun positions and tank turrets set in concrete, as well as mines, wire obstacles and anti-tank ditches.

The Allied plan called for a surprise attack upon the east flank, followed by a swing toward Bologna. To deceive the Germans into believing the attack would come in the west, the 1st Canadian Division was concentrated near Florence, then secretly moved northward to the Adriatic.

In the last week of August 1944, the entire Canadian Corps began its attack on the Gothic Line with the objective of capturing Rimini. On August 25, the Canadians crossed the Metauro River, the first of six rivers lying across the path of the advance. They moved on to the Foglia River to find that the Germans had concentrated their forces here. It required days of bitter fighting and softening of the line by Allied air forces to reach it.

On August 30, two Canadian brigades crossed the Foglia River and fought their way through the Gothic Line. On September 2, General Burns reported that; “the Gothic Line is completely broken in the Adriatic Sector and the 1st Canadian Corps is advancing to the River Conca.” The announcement was premature for the enemy recovered quickly, reinforced the Adriatic defence by moving divisions from other lines and thus, slowed the advance to Rimini to bitter, step-by-step progress. Five kilometres south of the Conca, the forward troops came under fire from the German 1st Parachute Division, while heavy fighting was developing on the Coriano Ridge to the west. By hard fighting, the Canadians captured the ridge and it appeared that the Gothic Line was finally about to collapse. The Canadians battled for three more weeks, however, to take the hill position of San Fortunato which block the approach to the Po Valley. San Fortunato was taken on 19 and 20 September by the 1st Division, and at last the Canadians looked down upon the Lombard Plain.

On September 21, the Allies entered a deserted Rimini. That same day, the 1st Division was relieved by the New Zealand Division, ready with the 5th Armoured Division to sweep across the Lombardy Plain to Bologna and the Po. But the rains came. Streams turned into raging torrents, mud replaced the powdery dust and the tanks bogged down in the swamp lands of the Romagna. The Germans still resisted.

September 1944 waned and with it the hopes of quickly advancing into the valley of the Po. On October 11, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division returned to the line and the 5th Division went into corps reserve. For three weeks, the Canadians fought in the water-logged Romagna. The formidable defences of the Savio River were breached, but the Germans counter-attacked to try to throw the Canadians back. Meanwhile, the Americans were progressing toward Bologna, and to halt their advance, the Germans took two crack divisions from the Adriatic front. The Canadians were thus able to move up to the banks of the Ronco, some ten kilometres farther on.

The Canadian Corps was now withdrawn into Army Reserve to recuperate from the ten weeks of continuous fighting and train for the battles which lay ahead. The 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade, meanwhile, continued to operate with the Americans and British in the area north of Florence. They would end their campaign in Italy in the snow-covered peaks in February 1945.

The Canadians returned to battle on December 1 as the Eighth Army made one last attempt to break through into the Lombardy Plain. In a bloody month of river crossings which resulted in extremely heavy casualties, they fought through to the Senio River. Here the Germans, desperate in their resistance, drew reinforcements from their western flank and, aided by the weather and topography, stopped the Eighth Army. In January 1945 the Senio became stablilized as the winter line, and in appalling weather both sides employed minimum troops as they observed each other from concealed positions.

For the Eighth Army commanders and staff, the Lombard Plain had long been seen as ‘the Land of the Lost Content’ – a great broad plain stretching to the horizon and beyond where armour could run riot, as it had in the Western Desert of blessed memory, driving the enemy before it like sheep to the slaughter. It was all a great self-inflicted delusion. The army went down into the Romagna, the southeast quadrant of the plain, and found it laced with rivers and canals, many of them channelled between steep embankments which inhibited tank movement as thoroughly as the southern hills and ridges had done, and made life inconceivably difficult for the decimated and embittered infantry.

Here the Canadians fought from one water obstacle to the next, from the Marecchia to the Fiumicino to the Rubicon to the Pisciatello to the Savio Bridgehead where Private E.A. “Smokey” Smith earned a Victoria Cross for close action with German armour on 22 October 1944. The sequence of river crossings carried on through to Dec, and after the Savio came the Ronco, the Lamone and the Capture of Ravenna on 4 December. The Senio followed, where the Canadians tried several times to effect a crossing. Once again, winter stalemate set in. The Canadians wiped out two German bridgeheads on the Senio in January, and settled in to wait.

Throughout 1944, the Allied forces in Italy managed to pin down 40 divisions there and in the Balkans, about 20% of the total German military ground forces, preventing their use in the Soviet Union, in Normandy, Southern France, the Scheldt, and the Ardennes.

The forces in Italy were relocated to North-West Europe in early 1945 in an administrative move known as Operation GOLDFLAKE.

CONCLUSION

There was no more serious fighting in Italy after I Canadian Corps sailed from Leghorn for southern France, en route to the Netherlands… of the 92,757 Canadian soldiers who served in Italy, more than a quarter became casualties. Nearly 5,500 were killed and almost 20,000 wounded, with another 1,000 taken prisoner. During the whole campaign, Allied casualties totaled about 190,000 in the American Fifth Army and 123,000 in the Eighth Army (including the Canadians). Approximately 435,000 German soldiers were lost, including 214,000 officially recorded simply as “missing”.

The Italian Campaign of World War Two began with the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 and ended, for Canada, in February 1945 when the 1st Canadian Division was redeployed from Italy to the Western Front to assist with the advance across Western Europe to Germany. The Italian Campaign was Canada’s first major ground participation in the Second World War in Europe and would cost 25,264 casualties, 5,900 of them fatal, over its course which, at its highest peak, saw over 76,000 Canadians serving in Italy.

History of the Devils Brigade (First Special Service Force)

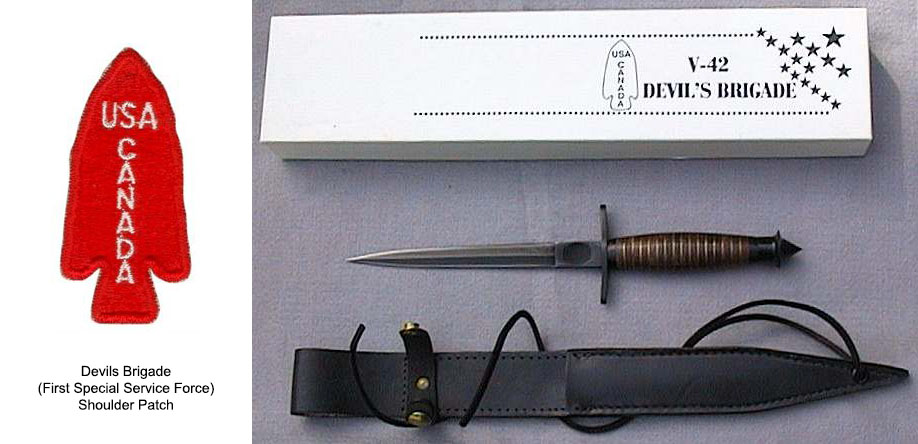

The Devils Brigade was a joint World War II American-Canadian commando unit trained at Fort Harrison near Helena, Montana in the United States. The volunteers for the 1600 man force consisted primarily of enlisted men recruited by advertising at Army posts, stating that preference was to be given to men previously employed as lumberjacks, forest rangers, hunters, game wardens, and the like. The 1st Special Service Force was officially activated on July 20, 1942 under the command of Lt. Colonel Robert T. Frederick. Force members received rigorous and intensive training in stealth tactics, hand-to-hand combat, the use of explosives for demolition, amphibious warfare, rock climbing and mountain fighting, and as ski troops. Their formation patch was a red arrowhead with the words CANADA and USA. They even had a specially designed fighting knife made for them called the V-42.

The Forcemen were issued special gear including specialized weapons, leather jackets, mountain climbing gear, parkas and other cold weather equipment. As an elite “commando type unit” that would operate near or behind enemy lines, the FSSF had a requirement for a special type of fighting knife. FSSF close quarters combat instructor, Dermot Michael “Pat” O’Neill, a former sergeant in the Shanghai Municipal Police Force, suggested the blade profile. O’Neill gave great thought to the needs of these special troops as it related to close quarters combat.

COL Orval J. Baldwin, FSSF supply officer, is credited with the skull crusher pointed pommel idea. Soldiers learned that the knife could be used either in a slashing or stabbing fashion. Part of FSSF training included classes on human anatomy; soldiers were taught how to bleed a man or quickly kill. Only members of the Combat Echelon of the FSSF were issued the knife. Forcemen took a great deal of pride in the V-42 knives as a symbol of an elite unit as well as a deadly fighting tool in its own right.

The V-42 featured a 7 5/16 inch blued stiletto blade, and had an overall length of 12 inches The handle was made of finely serrated leather washers and the pommel ended in a short point for use as a “skull crusher.” The knife was marked “CASE” on the ricasso, and a section of the rear blade near the blade shoulder was serrated for use as a thumb rest to help align the blade during a thrust. The V-42 was essentially a custom-made knife as opposed to the other types of mass-produced military knives that were made in the millions.

The knife was issued with a leather scabbard about 20 inches in length with thongs to be tied about the lower thigh. The reason for the length was so the knife would hang below long parkas and be instantly available. The scabbard was later equipped with a metal backing at the bottom, because the sharp tip of the stiletto-style knife often gouged its way into the Forcemen’s legs during training. The V-42’s relatively thin stiletto blade, which made it such an effective fighting knife, did not lend itself to use as a tool or camp implement.

So unique was the V-42 knife that it was incorporated into the first design for the coat of arms of the First Special Service Force flag manufactured in 1943. It is the only heraldic item to appear on the shield and a set of crossed arrows that make up the coat of arms. In 1960, when the First Special Service Force was reconstituted as the 1st Special Forces, the parent regiment for all Special Forces groups, the original coat of arms used by the FSSF was adopted by the 1st Special Forces. The shield of the coat of arms has never been changed. The distinctive unit insignia (better known as unit crest) of the 1st Special Forces still has the V-42 prominently displayed in the center of the design between two crossed arrows. It has been worn by Special Forces soldiers since 1960 when it was originally approved for wear.

The First Special Service Force was officially inactivated on 5 December 1944 in Villeneuve-Lobet, France. But the Case V-42 lives on to this day. In the U.S. Special Operations community, it is the symbol of many great accomplishments. The White Star Training Teams in Laos circa 1960-61 used the V-42 on their beret insignia. The 7th Special Forces Group Mobile Training Teams in El Salvador used the V-42 on their unofficial pocket patches. Numerous other patches and crests use this knife for their central character as a symbol of stealth and courage.

A few manufacturers have reproduced the V-42 over the years. The Force knife, with its slim shape, excellent handling, leather-ringed pommel and spike at the end has become a collector’s item not only because of its scarcity, but also because of its grace and balance. In 1942-1943, a V-42 cost only a few dollars to manufacture. Today, original V-42s often sell for thousands of dollars.

The V-42 is a legendary knife that today is an enduring symbol of the most elite of the U.S. Army. No article of equipment is as synonymous with the First Special Service as their V-42 Fighting Knife.

The Canadian part was originally the 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion, then renamed the 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion. In June 1942, when it joined with US Army troops and became the First Special Service Force, Canadians comprised 1/4 of its strength, 47 officers and 650 other ranks. Lt.-Col. J. G. McQueen returned from overseas to take command of the Battalion; the bulk of the personnel was selected on a voluntary basis from the Army in Canada, the junior officers being in the main recent graduates of the Officers Training Centre at Brockville, Ontario. All men accepted were required to be fully trained soldiers, and to volunteer for duty as parachute troops.

The First Special Service Force as organized consisted of a Combat Force and a Base Echelon or Service Battalion. Canada provided no men for the Service Battalion, but supplied, as already noted, about 700 all ranks for the Combat Force. Under the original “table of organization” this would have been about half the latter’s strength; but in practice the Force was always larger, and the Canadian component amounted to a little more than one-third of the Combat Force and a little more than one-quarter of the Force as a whole. The Commander of the. First Special Service Force from the beginning was Colonel Robert T. Frederick, U.S. Army. Lt.-Col. McQueen was appointed Second-in-Command of the Force. The Combat Force was organized in three “regiments” each of two battalions. Canadian and American soldiers alike were distributed throughout these regiments, not segregated in separate units.

The Canadians joined the Special Service Force at Fort William Henry Harrison (Helena, Montana) in August 1942, and parachute training was undertaken at once. During this training Lt.-Col. McQueen was injured and Lt.-Col. D. D. Williamson became the Force’s senior Canadian officer. When all members had qualified as parachutists, intensive ground training followed, and with the cold weather came training in winter warfare, under the advice of Norwegian instructors.

Training was arduous — parachuting, skiing, and mountain climbing. Everything was done “at the double” and their physical conditioning was aided by calisthenics, obstacle courses, and long marches with hundred-pound packs. Each man learned how to handle explosives and to use every weapon in the Force’s extensive arsenal. Hand-to-hand combat, night fighting, and use of captured weapons rounded out the training program. These specialized skills were necessary, for the Force members were to become shock troops, frequently raiding strategic positions and often parachuting behind enemy lines. Their effectiveness would earn them the nickname, “the Devils Brigade”.

The First Special Service Force arrived in Italy in November 1943, as the 5th U.S. Army was preparing to capture the mountains that guarded Cassino to the south. Its first task was to throw the Germans off two of the highest peaks, Monte la Difensa and Monte la Remetanea. Climbing ropes in the dense fog, the Force took the Germans by surprise on Difensa. Following a bloody, six-day battle, Monte la Remetanea was captured. Its first involvement in the Italian campaign cost the First Special Service Force 511 casualties, including 73 fatalities. The Force went into action again on Christmas Day east of Cassino. In the bitter mountain battles that followed frostbite and exposure caused as many casualties as the enemy.

A month later, the Force equaled its earlier accomplishment by taking Monte Majo and several other ridges controlling the Via Caslina, the main Naples-Rome road. In terrible weather and even harsher conditions, the Germans were forced back across the Rapido River valley to their main defences, the Gustav Line. Sixty-seven Canadian members of the Force were either killed or wounded on Monte Majo.

By the time the First Special Service Force was pulled out of the line in the middle of January, it had an impressive record. After securing Majo, it drove the enemy from Hills 1109 and 1270, and other Fifth Army formations cleared the Germans from east of Cassino. Due in large part to this elite Canadian-American unit, the Fifth Army was finally ready to launch its long-awaited offensive on Rome. The Force was now sent to Anzio.

During Operation Shingle at Anzio, Italy, 1944, the Special Force were brought ashore on February 1st, after the decimation of the U.S. Rangers, to hold and raid from the right-hand flank of the beachhead marked by the Mussolini Canal/Pontine Marshes, which they did quite effectively. Its Canadian component was the only Canadian unit to share the gruelling Anzio experience. A few reinforcements left it with a combat strength of 1,233, all ranks. Only one of its regiments was intact, the other two were at half-strength. The Force promptly took over one-quarter of Anzio’s thirty-mile-long front, and in a week forced the Germans to withdraw more than a mile from the Mussolini Canal, which was situated at the right flank of the bridgehead. It remained in position there, digging, fighting off counter-attacks, and being pounded by the German guns on the high ground overlooking our level and exposed positions, for fourteen weeks. It was finally relieved on 9 May.

Performing night raids, scouting and reconnaissance, one of the most successful Force soldiers was 28-year-old Canadian Tommy Prince from Manitoba, who became one of Canada’s most-decorated Aboriginal soldiers, with the Military Medal and the U.S. Silver Star for bravery in action. One of his most famous exploits, earning him the Military Medal, occurred near Anzio, where he calmly placed himself in great danger to report enemy artillery positions. It was at Anzio that the enemy dubbed the 1st Special Service Force as the “Devils Brigade.” The diary of a dead German soldier contained a passage that said, “The black devils (Die schwarze Teufeln) are all around us every time we come into the line.” The soldier was referring to them as “black” because the brigade’s members smeared their faces with black boot polish for their covert operations in the dark of the night.

Despite outstanding performances like this, the Force’s casualties at Anzio, while not heavy, mounted steadily. By the time it came out of the line on May 9, it had lost 384 men, killed, wounded, or missing, 117 of which were Canadian. Canadian and American members of the Special Force who lost their lives are buried near the beach in the Commonwealth Anzio War Cemetery and the American Cemetery in Nettuno, just east of Anzio.

By this time, the Force had spent nearly a hundred days in continuous action and so when it came out of the line at Anzio, was given an opportunity to rest and reorganize. Reinforcements strengthened the unit, including 15 Canadian officers and 240 other Canadian ranks.

The Special Service Force had particularly fierce fighting during the break-out from the bridgehead beginning on 23 May and was also heavily engaged during the subsequent advance to Rome. This was the period of its heaviest Canadian losses; from 1 May to 7 June casualties amounted to 18 officers and 194 other ranks. Additional reinforcements arrived later in June.

In late May, the Force headed toward Appian Way, one of the two highways to Rome from the south. Once again the members found themselves in the mountainous terrain in which they excelled and soon seized Monte Arrestino at the entrance to the valley leading northwards to Valmontone, then took Artena, near Valmontone. The approach to Rome began early morning on June 3 and by midnight, the Force had reached Rome’s suburbs. An hour later the Force commander was ordered to seize the Tiber bridges into the capital to prevent the Germans from blowing them up. During the night of June 4th, members of the Devils Brigade entered Rome. After they secured the bridges, and seized key locations in Rome’s centre, they quickly moved north in pursuit of the retreating Germans. The following morning, throngs of grateful Romans lined the streets to give the long columns of American soldiers passing through the city a tumultuous reception. War photographers captured the scenes of joy on film to be seen back home, but the soldiers of the Devils Brigade, who actually liberated the city had passed through Rome during the early morning hours in darkness and near silence and were again in fierce combat with the Germans along a twenty-mile front on the Tiber River.

By the time the “Devils Brigade” secured Rome, Canadian casualties alone totalled 185, or about one-third of the Force’s Canadian contingent. Sixty-two of them lie among the 2,313 war dead at Beach Head War Cemetery in Anzio on Italy’s west coast.

Following the taking of Italy, on August 14, 1944 the Brigade was shipped to Iles d’Hyères in the Mediterranean Sea just off the coast of Southern France. As part of the U.S. 7th Army, they fought again with distinction in many battles. On September 7th, they moved to the Franco-Italian border in what is called the “Rhineland Campaign.” Members of the Brigade, usually traveling by foot at night, made their way behind enemy lines to give intelligence on German positions. This operation not only contributed to the liberation of Europe, but the information Brigade members were able to pass back to headquarters saved many Allied soldier’s lives.

After a further period of amphibious training, the Special Service Force took part in August in Operation DRAGOON, the great assault of the Seventh Army on the south coast of France. Here again the Special Service Battalion was the only Canadian Army unit to take part in the operation, although the Royal Canadian Navy was well represented. The Force fought in a Commando role, landing in the early hours of 15 August on the islands of Port Cros and Levant east of Toulon. Its task was carried out with complete success in the face of fairly stiff opposition. Thereafter it took part in the rapid exploitation inland and early in September was close to the fortified Italian boundary. Here the Force halted and remained covering the Allied right flank until 28 November, when it was withdrawn.

The First Special Service Force was now disbanded, on the suggestion of the United States authorities, to which Canada agreed. A farewell parade was held on 5 December 1944; the Canadians parted from their American comrades amid mutual good wishes, and returned to Italy. Those men not trained as parachutists were used as infantry reinforcements for the Canadian force in that country. The balance of the personnel were sent back to the United Kingdom, where they became reinforcements for the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

The 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion officially ceased to exist on 10 January 1945. Thus ended a remarkable international experiment. The mixed composition of the Force had not prevented it from attaining an extraordinary regimental spirit; perhaps, indeed, it was in great part responsible for that spirit. Canadians and Americans have never found it hard to co-operate, and in the First Special Service Force they worked and fought together in a relationship which helped to make the Force the splendid fighting unit it was.

The Devils Brigade, a one-of-a-kind military unit that never failed to meet its goal, was disbanded by the end of the War. However, in 1952 Col. Aaron Bank would create another elite unit using the training, the strategies, and the lessons learned from the Devils Brigade’s missions. This force would evolve into specialized forces such as the Green Berets, Delta Force, and the Navy Seals.

In Canada, today’s elite and highly secretive JTF2 military unit is also modelled on the Devils Brigade. Like World War II, Canadian JTF2 members and American Delta Force members were united again into a special assignment force for the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan.

In September of 1999, the main highway between the city of Lethbridge, Alberta Canada and Helena, Montana in the United States was renamed the “First Special Service Force Memorial Highway.” This highway was chosen because it was the route taken in 1942 by the Canadian volunteers to join their American counterparts for training at Fort Harrison.

ITINERARY

Day 1: In the footsteps of the Devils Brigade (FSSF)– The battles for the Winter Line.

We will start our tour visiting the area where the Devils brigade were involved in December 1943: Monte la Defensa, La Rementana, Monte Sammucro were high points of the Winter Line fortified by the Germans

The key to the German defence in Italy was to control the high ground. The Germans from October 1943 started building their defensive lines to slow down the advance of the Allied forces.

South of Cassino the Germans built one of their defensive lines Bernhardt (or Reinhard) line named by the Allies “ Winter line” as they were fighting here during the winter months.

Today, we will learn about the heroism of the FSSF, the Devils brigade and the battles to break the Winter line. We will visit the key points of the winter line including the memorial for the FSSF, the Italian war cemetery and the deserted town of San Pietro Infine, the only town in Italy rebuilt in a different location so the old town is frozen to December 1943.

Day 2: Breaking the Hitler Line – Monte Cassino and the Liri valley

We will start our tour from a very symbolic location for the Canadians, the River Gari by the town of Sant’Angelo in Theodice when in May 1944 the Canadians built bailey bridges to advance to the Liri valley. Cassino fell to the Allies, after months of fighting, on 18th May 1944. Today, We will follow the advance of our brave Canadians from Cassino through the Liri valley.

23rd May was the longest day for the Canadians with over 1000 casualties, but they were finally able to break the Hitler line and advance to the old road to Frosinone, liberated on 31st May 1944.

We will visit the Commonwealth Cemetery, the Abbey of Monte Cassino, and exact copy of the destroyed one. We will follow the same route as the Canadians forces, From Monte Cassino through the Liri valley, stopping to honour the Canadians Memorials at Pontecorvo, Melfa river and Torrice crossroads, all important battles fought in May 1944.

Day 3: Ortona, the little Stalingrad

Today we will drive to the east coast to visit Ortona, on the Adriatic sector of the Gustav line.

The Gustav Line stretched across the narrowest part of Italy, coast to coast, from Minturno (west coast) to Ortona (east coast), incorporating mountainous terrain and fast flowing rivers.

In December 1943 in the little town of Ortona, called the little Stalingrad, for the kind of fighting, the Canadians met- desperate, determined German resistance.

Tank battles and house-to-house fighting raged through the streets for 8 long days. At the end, the Canadians were victorious, but this was clouded by a heavy cost: almost one quarter of the 5,900 Canadians killed during the Italian Campaign died in the fighting in and around Ortona, making it bloodiest battle of the Italian Campaign. We will pay our respects and visit the River Moro Canadian Cemetery and memorials to honour the brave Canadians soldiers

Day 4: Ciociaria- a Land to discover

Today we will explore the enchanting region of Ciociaria “Cho-cha-REE-a” one of the Italy’s few remaining ‘undiscovered areas. Beginning about 30 miles south east of Rome is a land of green, gumdrop-shaped hills, hill top towns and beautiful countryside.

Today, you will discover places that you probably never heard of but will never forget: perfectly preserved medieval centres, stunning landscapes, authentic food and wine.

Day 5: Anzio and the Devils brigade.

During Operation Shingle at Anzio, Italy, 1944, the Devils Brigade were brought ashore on February 1st, after the decimation of the U.S. Rangers, to hold and raid from the right-hand flank of the beachhead, marked by the Mussolini Canal/Pontine Marshes, which they did quite effectively. It was at Anzio that the enemy dubbed the 1st Special Service Force as the “Devils Brigade.” The diary of a dead German soldier contained a passage that said, “The black devils (Die schwarze Teufeln) are all around us every time we come into the line.” The soldier was referring to them as “black” because the brigade’s members smeared their faces with black boot polish for their covert operations in the dark of the night. We will see the Port of Anzio, the beaches of the Landings, the Sicily Rome American Cemetery and visit one of the largest WWII collections in Europe, with reconstruction in grand scale of the Italian campaign from Sicily to Rome.

Day 6: WWII tour in Rome: from the occupation to the liberation.

The first unit sent into Rome, the Devils Brigade were given the assignment of capturing seven essential bridges in the city to prevent the Germans from blowing them up. During the night of 4th June 1944, members of the Devils Brigade entered Rome. We will visit the plaques dedicated to them, have lunch in the same café were they used to go, over 72 years ago. A Cafè still owned by the same family: We will end our day at Villa Torlonia, where il Duce lived for almost 20 years. The Villa become one of the Allied headquarters, after the liberation of Rome 4th June 1944 until 1947 when it was abandoned. In 2006 it was restored to its splendour and opened year round for tours.

Day 7: Private tour of the Colosseum and Ancient Rome

Visit Rome’s historical headliners on this full-day priority tour that combines skip-the-line entrance to the Colosseum & Ancient Rome. Begin this private tour with the visit of the very icon of Rome: The Colosseum. After skipping the main entrance line with your priority-access ticket, you will be taken on a comprehensive walking tour of Ancient Rome – the Colosseum, the Roman Forum and Palatine Hill, recounting the intriguing and terrifying events which formed the Eternal City. Throughout your tour, enjoy in-depth commentary tailored to your interest.

- Due to new security procedures, when entering the Colosseum you may experience unexpected queues and baggage inspections.

Optional tours in Rome:

Vatican City: Vatican museums, Sistine Chapel and the Basilica of Saint Peter.

After a a short lunch break (or in a different day), you will visit the Vatican City.

Our classic highlights tour visits the Sistine Chapel, the Raphael Rooms and a diverse range of galleries covering ancient Greek and Roman sculptures, maps, tapestries and precious relics. From the Sistine Chapel we’ll use a special access door to gain entry directly to St. Peter’s Basilica*. This saves us from having to leave the Museums, walk 20 minutes to the general access entrance and wait for an hour in line. Inside the Basilica your guide will walk you through the stunning artworks held inside, the monumental carved altar and the incredible architecture of Christianity’s most iconic church.

This tour can be organized also early morning, before the opening hours to the public.

*Due to unforeseen circumstances beyond our control connected with the 2016 Jubilee Holy Year and Vatican urgencies, St. Peter’s Basilica and other religious sites may be subject to unscheduled last minute closures for religious ceremonies When this occurs, we will provide guests with an extended tour of the Vatican Museums, or appropriate alternative. Please note that appropriate dress is required for entry into some sites on this tour. Knees, shoulders and backs must be covered.

Optional tour: Catacombs, Crypts & Underground Rome

Descend into the subterranean layers of Rome’s fascinating and forgotten past

Our tour starts at one of the Roman Catacombs The tomb-lined tunnels of the catacombs stretch for miles and are many layers deep. Many of the first Christians buried here were later recognized as martyrs and saints. Others carved out niches nearby to bury their loved ones close to these early Christian heroes. While the bones are long gone, symbolic carvings decorate the walls: the fish stood for Jesus, the anchor was a camouflaged cross, and the phoenix with a halo symbolized the resurrection. By the Middle Ages, these catacombs were abandoned and forgotten. Centuries later they were rediscovered. Romantic-era tourists on the Grand Tour visited them by candlelight, and legends grew about Christians hiding out to escape persecution. But the catacombs were not hideouts. They were simply low-budget underground cemeteries.

Our tour discovering the wonders beneath Rome continues with the Basilica San Clemente were layers of history piled on top of each other so that visitors today climb down from a 13th century church to a 4th century church, to 2nd century remains of a Mithraic temple and finally ruins that date back to the Great Fire under the reign of Nero in 64 AD. Your journey through the centuries ends with one of the most memorable (and certainly the most original!) site we visit – the Capuchin Crypt and Museum. Here the remains of 4,000 Capuchin monks literally rest in pieces. Their remains have been used to decorate the underground crypt with vertebrae chandeliers, real-life skulls and cross-bones and robe-clad skeletons leering from the walls.

*Due to increased security measures at many attractions some lines may form on tours with ‘Skip the Line’ access.